Jobangst, Digitalisierung, politische Umwälzungen: Das abgelaufene Jahr war heftig. Die Erschöpfung ist gross – auch bei Topmanagern. Was ihnen zu schaffen macht und wo sie Hilfe finden.

Ein Auszug aus dem Text:

Ein Auszug aus dem Text:

In 1984, one year before the sci-fi classic “Back to the Future” was released, the professors Danny Miller and Peter Friesen from McGill University in Montreal published a seminal paper on corporate life cycles. Both works contained clairvoyant features for the future.

Building on an empirical sample of firms the paper titled “A longitudinal study of the corporate life cycle” describes how companies can be classified into five life cycles from birth to decline. The authors applied five dimensions to accomplish this task: strategy, structure, environment and decision making style.

Fast forward 30 years. The year 2015 which was vividly described in “Back to the Future Part II” has just passed and an entire economic sector, namely the banking industry, appears to be in the doldrums. Many banks seem to be in decline.

Do you work for a bank in decline? Let’s have a quick lock how Miller and Friesen verbatim characterized a declining firm along the four dimensions thirty years ago (emphasis added):

“Firms in the decline stage react to adversity in their markets by becoming stagnant […]. Firms seem to be caught in something of a vicious circle. Their sales are poor because their product lines are unappealing. This reduces profits and makes for scarcer financial resources, which in turn cause any significant product line changes to seem too expensive. So product lines become still more outdated […]; the firms just muddle through.”

“[…] There is a tendency to attend to what the owners want, that is, to preserve resources, rather than cater to the needs of customers. The market scope of declining firms is quite narrow […]. Failure in one major product line simply cannot be counterbalanced by success in others as might happen in more diversified companies […]. Shrinking markets can be extremely competitive and firms that rely totally upon them may find themselves in deep trouble. Performance thus tends to be very poor. This may be caused partly by the simple structure.”

“The locus of decision-making power is at the top of the firm. In fact, even routine operating decisions (these predominate in declining firms which shy away from strategic decisions) are executed by higher level managers […]. While managers who are close to customers and markets may be well aware of the problems that exist, their information does not seem to filter up to those with enough authority to do anything about it.”

“Decision making is characterized by extreme conservatism. There is little innovation, an abhorrence of risk taking, and a reluctance even to imitate competitors’ innovations, let alone lead the way […]. Sometimes it is due to the temperament of the top managers. Occasionally, it results from funds shortages stemming from previous declines in performance. But almost inevitably, key contributing factors are ignorance of markets […]. Managers fail to delegate and there is little in the way of participative management. Thus the top executives must spend most of their time handling crises. They just haven’t the time for much analysis. So they take very few dimensions into account in decision making […] and employ very short time horizons.”

This rich description of a declining firm crafted in the year 1985 may resonate with many people across the globe working for banks in the year 2016. If it rings a bell with you, your bank may well be in decline. However, not all hope is lost: in their empirical study Miller and Friesen also showed that 42% of the firms in the decline phase progressed to the revival phase. But don’t get your hopes up too soon: Miller and Friesen describe the survivor bias as one of the major shortcomings of their study. Their empirical study only contained surviving firms. Those which did not make it through the decline phase were not included in their research.

Unfortunately, it appears as if Miller and Friesen’s 1984 description of declining firms had quite some clairvoyant features for many a bank of the year 2016.

Source:

Miller, D., & Friesen, P. H. (1984). A longitudinal study of the corporate life cycle. Management Science, 30(10), 1161-1183.

Dr. Patrick Schüffel, Professsor, Institute of Finance, Haute école de gestion, Fribourg Chemin du Musée 4, CH-1700 Fribourg, patrick.schueffel@hefr.ch,www.heg-fr.ch

Feel free to check out further posts on www.schueffel.biz

Bundling will be the next big Fintech topic after unbundling and platformization. Just as consumers got used to buying different food items at one single supermarket long time ago, they will expect one-stop-shops for financial services. Those “bundlers” that manage to seamlessly offer cost-efficient and dynamic bundles are well poised for success in this next race in the Fintech arena. Some important lessons can be learned from previous bundling attempts, such as Deutsche Bank’s “Moneyshelf”.

In 2002 Deutsche Bank started an immensely ambitious e-commerce project. The objective of the project by the name of „Moneyshelf“ was to establish a financial super market. The goal was to create a one stop shop for virtually any financial product a retail client could wish for – across any provider existing. The underlying idea was to provide off the shelf financial products from any makers and brands. The reasoning behind it was that consumers would also frequent supermarkets to conveniently buy various products across brands and manufacturers. A modern consumer would visit a single supermarket to purchase bread, sausages, apples, beverages, canned food and cleaning liquid. He or she would no longer go through the ordeal of visiting a bakery to buy bread, a butcher to shop for sausages, a local market to get some apples and then drop by yet another store to buy beverages and food before visiting the local drug store to buy cleaning liquid.

Creating a financial supermarket

In order to use such a financial supermarket the client was requested to deposit his access information to any other banking service with the Moneyshelf platform. Moneyshelf would then let the client consolidate and manage all of his or her accounts in one highly user-friendly frontend. In the background online banking interfaces programmed by Deutsche Bank developers would ensure the interoperability. Moneyshelf promised a quantum leap in transparency and price efficiency. A client who would have a securities account with bank A and be invested in mutual funds from fund provider B could then not only shop for a more cost-efficient securities account, but also a better performing and less costly mutual fund und would only be a mouse click away. All of this was paired with features such as personal financial planners which offered insights on the clients’ spending and financial behavior and a rich offering of financial information and possibilities of analysis.

Deutsche Bank ahead of times

Moneyshelf as it was envisioned by Deutsche Bank was offering the client a tremendously versatile platform to choose among a vast range of providers and products such as current and savings accounts, mutual funds, brokerage services, mortgages, even life insurances. Deutsche Bank sensed that clients would become more tech savvy and consider the threat to be very real that Deutsche Bank may soon be disintermediated as far as their retail segment was concerned. With the emergence of online brokers and their strong growth Deutsche Bank feared of getting skinned and decided to take the bull by the horns. Hence, should a client decide to do business with a different bank, then Deutsche Bank would make sure that it would at least get a share of those revenue streams bypassing them.

The bone of contention: depositing client data

In the end this business model failed big time. The other banks, especially the rather dominant German savings banks warned their clients that it would be a violation of their contractual obligations to deposit account access information with any third party, including Moneyshelf. The savings banks maintained that they would not only refuse any liability in case of fraud, but that they would reserve the right to cancel the banking relationship with the client altogether should he or she access the account via Moneyshelf. Moreover the marketing campaign for Moneyshelf which depicted procreating animals was not very appealing to a largely conservative German retail banking segment.

Bundling as the central value propostion

Yet, Deutsche Bank got something right: the topic of bundling. As much as Fintech is about unbundling of banking services, a convenience loving customer does not want to sign up with Fintech Firm A to buy DJI stocks, with Fintech company B to convert some FX and with Fintech enterprise C to set up a financial plan. The levels of user experience and thus user expectations have never been higher than today. Hence, the emancipated banking client of nowadays would expect all of these services offered by one single provider and being accessible via one user interface (UI). Banking platforms such as N26, Moven, Bankin’ and Simple prove that the theme of bundling is highly topical as they oftentimes put together the services of a range of Fintech firms and offer them seamlessly through one UI.

The sophisticated future of bundling

However, the future of bundling will be much more sophisticated than that. Clients will expect not only expect cost-efficient but dynamic bundles. For instance, whereas payment provider A may be ideal for one money transfer from country X to country Y, it maybe payment provider B for the next transaction. Clients will not care which contractual obligations the platform is tied to, but the customer will expect the most cost-efficient Fintech firm to take over the task at hand. The same goes for stock brokerage or financial planning. The client will rightly demand to execute via the most cost-efficient broker and to set-up the financial plan with that one Fintech firm he or she sees most suitable. It will be the task of the platform owner or “bundle”, to tap into the Fintech eco-system to always find the most suitable service provider. The bundler must to put together these services for the consumer seamlessly and in a highly transparent fashion.

The race for bundling is on

The race for the best bundler will be open to Fintech firms and incumbent banks alike. This time, however, banks will no longer have a head-start for two reasons: first, a range of highly professional financial data aggregators such as eWise exist nowadays which can provide the necessary services off-the-shelf. Secondly an overhaul of EU legislation will update the rights and responsibilities of account information service providers, permitting intermediaries to obtain the account access information from clients. This change in legislation will come into effect in 2018 and it will be the starter’s gun for a European bundlers’ race in financial services.

Dr. Patrick Schüffel, Professsor, Institute of Finance, Haute école de gestion, Fribourg Chemin du Musée 4, CH-1700 Fribourg, patrick.schueffel@hefr.ch, www.heg-fr.ch

Moneyshelf ad

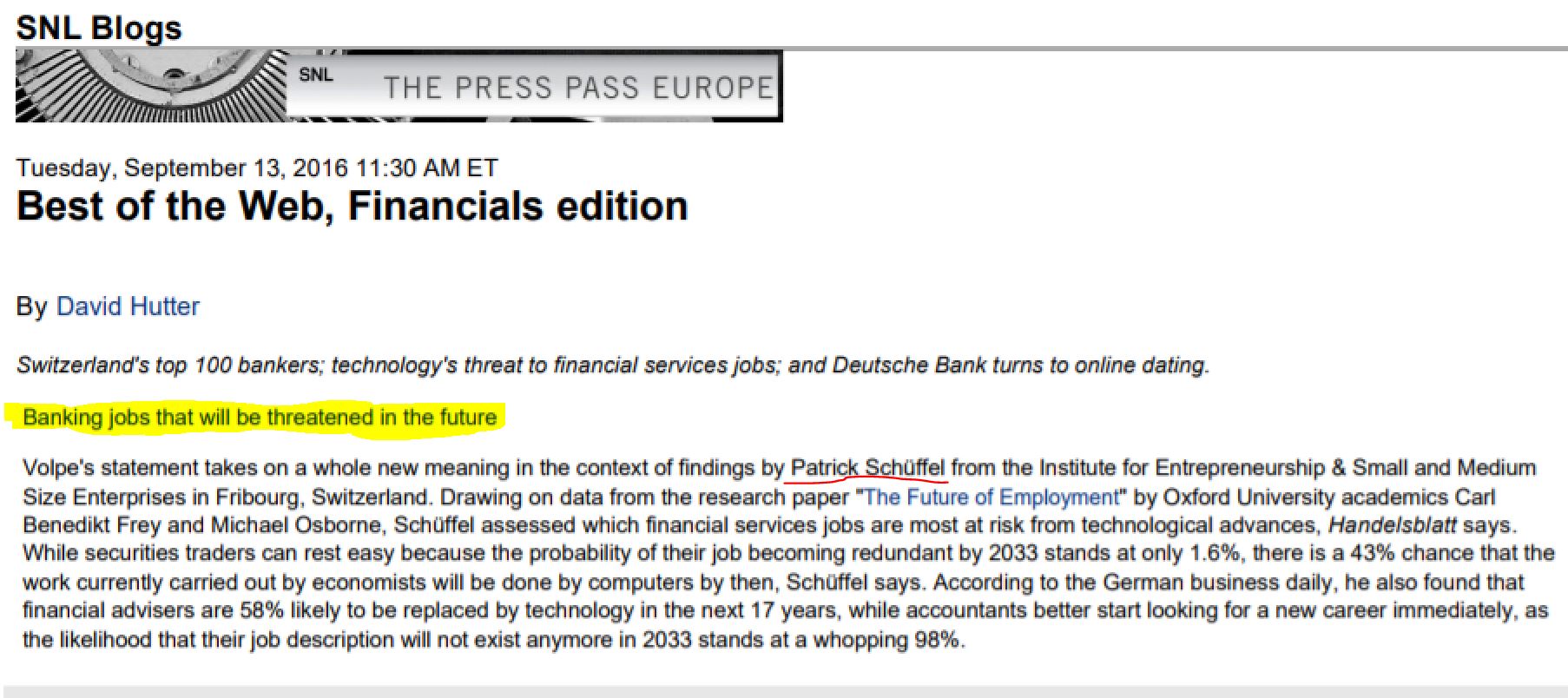

If you want to read the complete edition of Best of the Web, Fiancial edition 13. Sep 2016, click here.

If you want to read the complete edition of Best of the Web, Fiancial edition 13. Sep 2016, click here.

The full article can be accessed here. (German only)

Dr. Patrick Schüffel, Professsor, Institute of Finance, Haute école de gestion Fribourg, Chemin du Musée 4, CH-1700 Fribourg, patrick.schueffel@hefr.ch, www.heg-fr.ch

Nr. 168 vom 31.08.2016 Seite 030

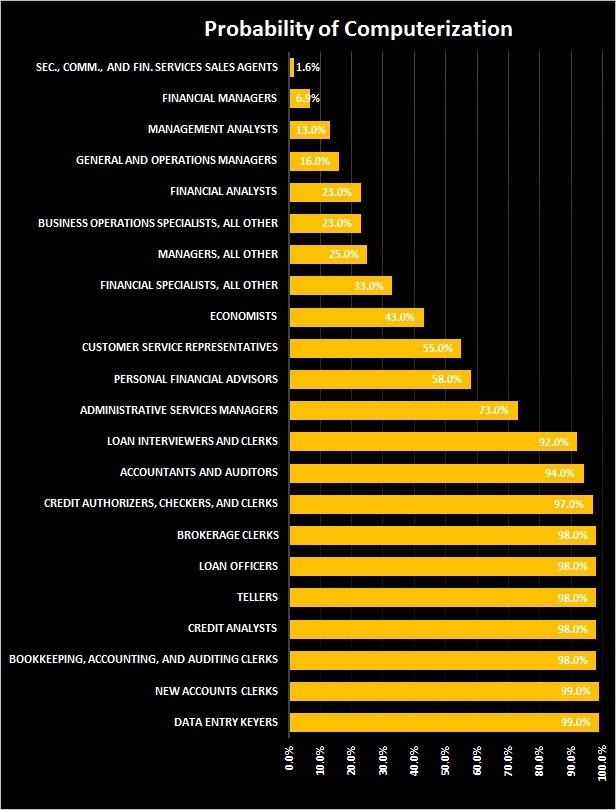

Sie sind, mit ihrer Mischung aus hochkompliziertem Denken, Intuition und mitunter leidenschaftlich verteidigten Grundsätzen, sozusagen die Theologen des Kapitalismus: die Ökonomen. Kaum ein Berufsstand im Bankbereich genießt so hohes intellektuelles Ansehen. Nirgendwo sonst spielt akademisches Denken im Geschäft eine vergleichbar große Rolle. Aber wie wahrscheinlich ist es, dass auch im Jahr 2033 Banken noch Ökonomen beschäftigen? Nach Meinung von Patrick Schüffel, Finanz-Professor im schweizerischen Freiburg, wird dieser Job zwischen 2023 und 2033 mit einer Wahrscheinlichkeit von 43 Prozent vom Computer übernommen. Ein Beispiel dafür, dass der digitale Kollege, der uns in den letzten Jahren mehr und Routinearbeit abgenommen hat, künftig auch intellektuelle Aufgaben übernimmt.

Schüffel stützt sich bei seiner Prognose auf eine Arbeit von Carl Benedikt Frey und Michael Osborne mit dem Titel “The Future of Employment”. Darin haben die beiden Wissenschaftler, gestützt auf offizielle Jobbeschreibungen der US-Regierung, 702 Berufe untersucht. Sie prüften mit einem mathematischen Modell, das auf Basis bisheriger Trends Prognosen erstellte, die Wahrscheinlichkeit des Verschwindens von Jobprofilen. Ihre Schlussfolgerungen sind dramatisch: “Nach unseren Schätzungen sind 47 Prozent der Stellen in den USA einem hohen Risiko ausgesetzt. Das heißt, die entsprechenden Tätigkeiten können irgendwann in der Zukunft, vielleicht in zehn oder 20 Jahren, automatisiert werden.”

Schüffel hat gezielt die Daten für die Bankbranche für das Jahrzehnt bis 2033 aus der Studie herausgezogen. Die Ergebnisse zeigen eine große Bandbreite. So liegt die Wahrscheinlichkeit, dass Verkäufer im Wertpapierbereich überflüssig werden, bei nur 1,6 Prozent. Auf der anderen Seite sind “persönliche Finanzberater” mit 58 Prozent Risiko in hohem Maße bedroht. Noch schlimmer sieht es für Leute aus, die lediglich per Hand Daten erfassen: Mit 99 Prozent Risiko hat der Beruf kaum eine Überlebenschance. Dasselbe gilt aber mit 98 Prozent auch für Buchhalter und Kreditsachbearbeiter. Zum Teil enthält die Aufstellung allerdings kaum erklärbare Differenzen: Finanz-Analysten sind nur zu 23 Prozent bedroht, Kredit-Analysten dagegen zu 98 Prozent.

Das letzte Beispiel zeigt die Grenzen derartiger Prognosen. Letztlich handelt es sich um Gedankenspiele, bei denen der eigentliche Wert weniger in den Prozentzahlen liegt als darin, Denkanstöße zu geben. Ein wichtiger Punkt ist dabei: Arbeiten, die allein eine hohe abstrakte Intelligenz erfordern, gelten als durchaus ersetzbar. Je mehr hingegen soziale Intelligenz und Kreativität gefragt sind, desto weniger Chancen hat Kollege Computer. Daher sind Verkäufer schwer zu ersetzen, auch wenn sie vielleicht weniger abstrakte Intelligenz brauchen als Ökonomen.

Soziale Kompetenz als ein Ausweg Ausschlaggebend für die Einschätzung der jeweiligen Berufe ist daher, wie die damit verbundenden Aufgaben eingeschätzt und gewichtet werden. Besteht die Aufgabe des Ökonomen vor allem darin, eine Konjunkturprognose für das nächste Quartal abzugeben? Dann hat der Kollege Computer eine gute Chance, ihn abzulösen. Schon heute gibt es Unternehmen wie etwa Now-Cast, bei denen selbstlernende Software kurzfristige Prognosen übernimmt. Oder besteht die Aufgabe der Ökonomen eher darin, Daten zu erklären und Rahmenbedingungen für die wirtschaftliche Entwicklung zu analysieren? Da tut sich der Computer schon schwerer. Viele Bank-Ökonomen arbeiten zudem de facto in der Kundenbetreuung. Sie unterhalten sich mit Großkunden über ökonomische Fragen.

Das dient nicht nur dazu, harte Schlussfolgerungen, etwa für Investitionen, logisch abzuleiten. Anleger, die ihre Entscheidungen unter hoher Unsicherheit treffen müssen, suchen versierte Gesprächspartner, mit denen sie die Last dieser Unsicherheit teilen können. Bei dieser Aufgabe ist das persönliche Gespräch durch nichts zu ersetzen, nicht einmal durch Videokonferenzen, geschweige denn den Computer.

Das Beispiel zeigt, dass der Computer viele Berufe nicht ersetzt, sondern sie verändert und die Gewichte verschiebt. So gibt es etwa bei freien Finanzberatern in den USA den Trend, Anlage-Entscheidungen tatsächlich Computern, den sogenannten Robo-Advisern, zu überlassen. Kernaufgabe des Beraters ist dann nicht mehr, dem Kunden einen angeblich heißen Aktientipp zu geben. Vielmehr muss der Dienstleister helfen, eine Einschätzung seiner finanziellen Situation und Risikobereitschaft herzuleiten. Diese kann dann Grundlage für die maschinelle Verwaltung eines Depots werden.

Heute schon gibt es auch Firmen, die vom Handel an den Kapitalmärkten leben, ohne einen einzigen Händler zu beschäftigen. Die Aufträge werden vom Computer erledigt. Aber die jeweilige Software entsteht in Zusammenarbeit von Computer- und Kapitalmarktexperten. Für viele Banker dürfte gelten, was Frey und Osborne als Schlussfolgerung ziehen: “Damit Beschäftigte das Rennen gewinnen, müssen sie kreative und soziale Kompetenz erwerben.”

ZITATE FAKTEN MEINUNGEN

Nach unseren Schätzungen sind 47 Prozent der Stellen in den USA einem hohen Risiko ausgesetzt. Carl Benedikt Frey, Michael Osborne Professoren in Oxford

https://www.financial-career-bw.de/news-events/news/detailansicht/artikel/welche-bankjobs-der-computer-uumlbernimmt/

Common wisdom had it that one’s job would be secure if one was well educated and kept up-to-date on the job. Now, however, we are increasingly facing a situation when even highly sophisticated occupations such as personal finance advisors as well as accountants and auditors will fall prey to digitalization.

In their 2013 study “The Future of Employment” Karl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne estimated the probability of computerization for 702 professions based on three factors: perception and manipulation tasks, creative intelligence tasks and social intelligence tasks.

Of those occupations examined by Frey and Osborne I have extracted those that I find relevant to the banking industry. The percentage figure displayed indicates the likelihood of that profession being computerized in “a decade or two”, i.e. between 2023 and 2033.

Sec., Commod., and Fin. Services Sales Agents: 1.6%

Financial Managers: 6.9%

Management Analysts: 13.0%

General and Operations Managers: 16.0%

Financial Analysts: 23.0%

Business Operations Specialists, All Other: 23.0%

Managers, All Other: 25.0%

Financial Specialists, All Other: 33.0%

Economists: 43.0%

Customer Service Representatives: 55.0%

Personal Financial Advisors: 58.0%

Administrative Services Managers: 73.0%

Loan Interviewers and Clerks: 92.0%

Accountants and Auditors: 94.0%

Credit Authorizers, Checkers, and Clerks: 97.0%

Tellers: 98.0%

Loan Officers: 98.0%

Credit Analysts: 98.0%

Brokerage Clerks: 98.0%

Bookkeeping, Accounting, and Auditing Clerks: 98.0%

New Accounts Clerks: 99.0%

Data Entry Keyers: 99.0%

Dr. Patrick Schüffel, A.Dip.C., M.I.B., Dipl.-Kfm.

Professsor

Institute of Finance

Haute école de gestion Fribourg

Chemin du Musée 4

CH-1700 Fribourg

patrick.schueffel@hefr.ch, www.heg-fr.ch

Increasingly often I am being asked by students, colleagues, investors, even friends and family “What is Fintech?”. I then typically answer “Fintech is an industry made up of organizations using novel financial technology to support or enable financial services”. And then, to avoid misunderstandings I add “A Fintech is an organization that uses novel financial technology to support or enable financial services”.

Increasingly often I am being asked by students, colleagues, investors, even friends and family “What is Fintech?”. I then typically answer “Fintech is an industry made up of organizations using novel financial technology to support or enable financial services”. And then, to avoid misunderstandings I add “A Fintech is an organization that uses novel financial technology to support or enable financial services”.

Yet, what sounds like a pretty straight-forward answer, was a hard nut to crack. In fact, the term Fintech is so often and widely used that some people even increasingly shun using it altogether.* To them the concept of Fintech has become too comprehensive and too ubiquitous to have any conclusive meaning any longer. For me it required quite a thought process to come up with a telling definition. This is due to several reasons.

First, a definition is never true or false per se, but more or less useful in a specific context. For instance, think about the term “power”. How would a physicist define it? How a politician? Which definition would a judge provide? Which explanation would an athlete give? Moreover, even within the domain of sports you are likely to receive different answers, depending on whom you ask. A weight lifter will most probably provide you with a different answer is than the fellow athlete from the same Olympic team who competes in synchronized swimming. Hence, we have to accept that – contingent on the counterparty you ask – one may well receive varying answers on the identical question. The same applies to the expression Fintech.

Looking at the most popular encyclopaedia of our times, Wikipedia, we can read that “[f]inancial technology, also known as fintech, is an economic industry composed of companies that use technology to make financial services more efficient.” (Wikipedia, 2016a). Conveniently enough for the reader, Wikipedia also provides us with the source for their definition. Wikipedia refers to the Wharton FinTech Club which provided this definition (Wharton Fintech, 2014). In a similar vein Susanne Chishti and Janos Barberis state in their landmark book on Fintechs that “Financial Technology or FinTech is one of the most promising industries in 2016” (Chishti & Barberis, 2016, p.5). The Oxford Dictionary tells us that Fintech is a mass noun (Oxford English Dictionary, 2016). More specifically this most authoritative source for British English suggests that Fintech are “Computer programs and other technology used to support or enable banking and financial services: fintech is one of the fastest-growing areas for venture capitalists”. In this context it may also be noteworthy that the most widely used dictionary and thesaurus for American English, Merriam-Webster, does not offer any definition for the term (Merriam-Webster, 2016).

On one popular Web sites in the Fintech sphere one can find the following definition “Fintech is a line of business based on using software to provide financial services.” (Fintech Weekly, 2016). Interestingly enough on that very Website reference is made to Wikipedia which – at least today – provides a different definition. On another blog from the finance world one can read a definition provided by Harry Wilson of Claro Partners: ”FinTech is an ecosystem of startups” (Wilson, 2015).

We could almost indefinitely continue this exercise of extracting definitions for the term Fintech from various authors. Yet, already from this very short although not representative selection of definitions, we can conclude that there is a vast range of meanings of the word Fintech: from “computer programs” and “other technologies” over “line of business” and “ecosystem” to an “industry”. This plethora of connotations makes it hard, if not impossible, to distil one commonly accepted explanation.

Interestingly enough even some of the biggest consultancies which certainly employ some of the smartest minds on the planet shy away from defining the term Fintech. Regularly one can find reports on Fintech related topics which do not provide any definition of the term Fintech itself; see for instance the McKinsey report on the effects of Fintech on banks by Dietz, Khanna, Olanrewaju & Rajgopal (2015) or the BCG report on the opportunities Fintech provides to corporate banks by Dany, Goyal, Schwarz, Berg, Scortecci & Baben (2016).

The second reason, why it is so inherently difficult to define the concept of Fintech is because definitions change over time. Also here we have some analogies. As an illustration think about the expression “information technology” (IT). In the early days of computing IT stood for items such punched tapes and cathode ray tubes. Today, however, we much rather associate things such as Motion User Interfaces, Bots and the Internet of Things with IT. Consequently, it is also safe to assume that the expression Fintech undergoes change. The definition provided by Investopedia pays tribute to this fact: “Fintech is a portmanteau of financial technology that describes an emerging financial services sector in the 21st century. Originally, the term applied to technology applied to the back-end of established consumer and trade financial institutions. Since the end of the first decade of the 21st century, the term has expanded to include any technological innovation in the financial sector, including innovations in financial literacy and education, retail banking, investment and even crypto-currencies like bitcoin.” So, for the authors of Investopedia, Fintech was originally an expression describing banking backend technology, but widened over time to also encompass technological innovations in financial services and related areas (Investopedia, 2016). Following the authors of Investopedia Fintech is not just a mere industry, but also a technology and an expression for innovation.

So far we have been talking about “Fintech” – without prefixed article. However, during conversations, but also in texts one also regularly encounters the expression “a Fintech”. Is there a difference between “Fintech” and “a Fintech”? If so, what is the difference? To my experience people typically refer to a Fintech company or more specifically to a Fintech start-up when they talk about “a Fintech”. Hence, the difference is the “level of analysis” as the scientist would say. As explained above “Fintech” without article typically relates to an entire a group of objects whereas “a Fintech” is just one single entity. This apparently small difference by the prefix “a”, can give rise to serious misunderstandings. To a politician, for instance, it will make a world of difference, whether he or she is asked to support creating an industry cluster or even entire industry or just one single firm. The same goes for a venture capitalist albeit with opposite signs.

Fourth and last, confusion about the term Fintech emerges from the fact that definitions can vary across languages. To illustrate this fact, I recommend to take a look at the various definitions of Fintech provided by different language versions of Wikipedia. The Italian site, for instance, states that Fintech is the “provision” of financial products and services using information technologies [“La tecnofinanza, o tecnologia finanziaria (in inglese Financial Technology o FinTech) è la fornitura di servizi e prodotti finanziari attraverso le più avanzate tecnologie dell’informazione (TIC)”] (Wikipedia, 2016b).

By contrast, the German Wikipedia definition of Fintech suggests that Fintech is an umbrella term for “modern technologies in the area of financial services” [“Finanztechnologie (auch verkürzt zu Fintech bzw. FinTech) ist ein Sammelbegriff für moderne Technologien im Bereich der Finanzdienstleistu ngen”] (Wikipedia, 2016c).

The French Wikipedia version is much closer to the English one, yet it does not define Fintech as an industry, but more loosely as an “area of activity” [“La technologie financière, ou FinTech, est un domaine d’activité dans lequel les entreprises utilisent les technologies de l’information et de la communication pour livrer des services financiers de façon plus efficace et moins couteuse”] (Wikipedia, 2016d).

Hence, just by comparing across languages one can already fathom the potential for misunderstandings. While the Frenchman may be talking about Fintech as a business segment, the German may be speaking about technologies, the Italian about a delivery channel and the native English speaker may refer to an entire industry. Being aware of potential pitfalls is all the more important as the term Fintech is derived from the English words Financial Technology and also used as such in various other languages. Thus people may automatically assume that they talk about identical things whilst they are not. In addition one should bear in mind that Fintech is a global phenomenon. Running into questions of semantics across languages may happen easier than anticipated.

However, we can live with this ambiguity in definitions. In fact we have been living with this ambiguity for years, if not decades, in other fields of business and academia. For example, think about the term “strategy”, “innovation” or “business model”. We use them on a daily basis, yet we have not established one common definition for any of them. Hence, having not one single definition for the word Fintech has not and should not prevent us from using it. However, when talking about Fintech we should make clear to our audience what we mean by Fintech. Providing a little explanation for our audience may therefore significantly improve the efficiency of communication and reduce the potential for misunderstandings. If you want to be extra polite you may also want to explain to your vis-à-vis why you use one specific definition and not another.

Once more I want to stress that none of the definitions provided above are right or wrong as such. Rather than that they are more or less useful in certain contexts. The definition I provided above, “Fintech is an industry made up of organizations using novel financial technology to support or enable financial services”, is very similar to the one provided by the Wharton Fintech Club and which is being promoted by the English Wikipedia site. Yet, I prefer to use the more broadly defined word organization instead of company. Companies are typically profit seeking and hierarchically organized. More and more often, however, we see non-hierarchical organizations such as The DAO to play a major role in the Fintech domain (The DAO, 2016). I purposely want to include these organizations in my definition. What is more, I tightened my definition in comparison to the Wharton definition by extending it for the word “novel”. I did this because otherwise the more comprehensive Wharton definition would also include just any incumbent bank running on Cobol-coded host systems as they are using this (admittedly ancient) technology to be more efficient. Lastly, I added the verb enable to my definition of Fintech as I am convinced that Fintech is not just about enhancing efficiency, but also more fundamentally about enablement. The distributed ledger rendered possible by Blockchain technology or micropayments made available through telecommunication systems are just examples for theses empowering technologies. Attention should be paid to the fact that innovation emanating from Fintech can be anything from purely complementary to highly disruptive. If the innovation is barely supporting an existing business model in financial services it is likely to be complementary, whereas it will receive the label disruptive if it jeopardizes existing business models.

I am well aware of the fact that the definition I use is far from perfect. For instance, it does not provide definitions for its components. Hence, one could rightly ask, “So what do you specifically mean by ’industry’ and what by ’novel’”? And how do you delineate ’industry’ from ’ecosystem’?”. Moreover I am certain that also the definition I use nowadays will change over time with the advancement of technology and the evolution of business. Last but not least, there are many terms up and coming that constitute for spin-offs of the overall Fintech theme. Among those are “InsurTech”, “WealthTech”, “RegTech”, just to name a few. Time will show how are they will be used.

Nicolas Steiner, one of the founding members of Level39 recently shared an anecdote about a meeting with a couple of French speaking experts from the telecommunication industry who asked him whether Fintech stood for “the end of technology”. The reasoning for that being that they believed that Fintech was short for the French expression “la fin de la technologie”. I hope by providing and spreading sense making definitions of Fintech we will encounter less and less of such misunderstandings in the future.

Spiros Margaris, who is often referred to as one of the Key Influencers of Fintech scene, once stated “Fintech will never disappear, only some fintech startups will disappear.” No matter which definition was used here, it is almost safe to say that this statement will come true.

*At this point greetings go out to Nasir Zubairi who is considered to be one of the big Fintech minds of Luxembourg

Chishti, S., & Barberis, J. (2016). The FinTech Book: The Financial Technology Handbook for Investors, Entrepreneurs and Visionaries. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Dany, O., Goyal, R., Schwarz, J., Berg, P. v. d., Scortecci, A., & Baben, S. t. (2016). Fintechs may be corporate banks’ best “Frenemies”.

Dietz, M., Khanna, S., Olanrewaju, T., & Rajgopal, K. (2015). Cutting through the FinTech noise: Markers of success, imperatives for banks. In G. B. Practice (Ed.): McKinsey & Company,.

Fintech Weekly. (2016). Fintech Definition. Retrieved from https://www.fintechweekly.com/fintech-definition

Investopedia. (2016). Fintech. Retrieved from http://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/fintech.asp

Merriam-Webster. (2016). fintech.

Oxford English Dictionary. (2016). fintech. Retrieved from http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/fintech

The DAO. (2016). Overview. Retrieved from https://daohub.org/about.html

Wharton Fintech. (2014). What is FinTech? Retrieved from https://medium.com/wharton-fintech/what-is-fintech-77d3d5a3e677#.kczb2jawk

Wikipedia. (2016a). Financial Technology. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Financial_technology

Wikipedia. (2016b). Tecnofinanza. Retrieved from https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tecnofinanza

Wikipedia. (2016c). Finanztechnologie. Retrieved from https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Finanztechnologie

Wikipedia. (2016d). Technologie financière. Retrieved from https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Technologie_financi%C3%A8re

Wilson, H. (2015). The new shape of FinTech is making the world a better place. Retrieved from https://www.finextra.com/blogposting/11518/the-new-shape-of-fintech-is-making-the-world-a-better-place

Professor Dr. Patrick Schüffel

patrick.schueffel@hefr.ch

Haute école de gestion Fribourg

Institute of Finance

Chemin du Musée 4

CH-1700 Fribourg

[posted on LinkedIn on July 20th]

Personally, I give Bill Gates credit for many a thing. Without his technology vision and his business acumen our daily lives would look totally different today. Yet, despite many sources on the Web claiming so, I give him no longer credit for the statement “Banking is necessary. Banks are not.”. After some tedious research on the Internet as well as in literature data bases the most convincing source of this quote became for me the former chairman and CEO of Wells Fargo, Mr. Richard M. Kovacevich. See Nocera, Joseph (1998): Banking is necessary-Banks are not. Fortune. May 11th, Vol. 137, Issue 9, p.84.

However, should you have any hard evidence proving the opposite, please do drop me a comment. Thanks!

Dr. Patrick Schüffel, A.Dip.C., M.I.B., Dipl.-Kfm.

Adjunct Professsor

Haute école de gestion Fribourg

Chemin du Musée 4

CH-1700 Fribourg

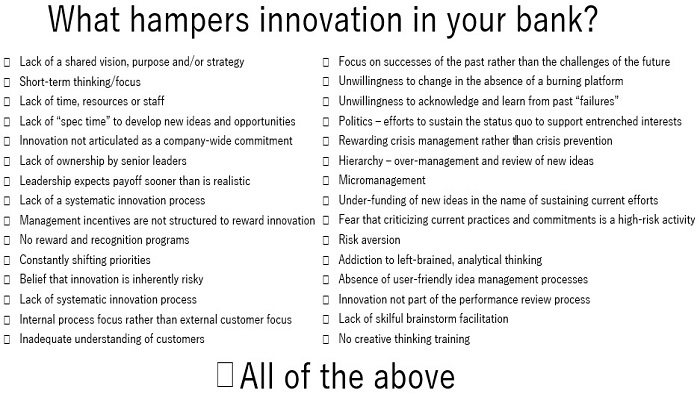

Innovating is intrinsically difficult. Coming up with an idea for a new service or product is just the mere beginning of what oftentimes turns out to be an extremely cumbersome journey. Moreover, the banking industry in particular is not especially innovation friendly. Being aware of obstacles on the road can help to clear those hurdles. So, whenever you enter on an innovation journey, spend a few minutes thinking of potential causes for troubles.

Dr. Patrick Schüffel, A.Dip.C., M.I.B., Dipl.-Kfm.

Adjunct Professsor

Haute école de gestion Fribourg

Chemin du Musée 4

CH-1700 Fribourg